Wearable Tech Provides Data-Driven Mental Health Therapy

Psychotherapists Partner with Algorithms to Improve Mental Health Treatment

After Chryssoula K.’s mother was diagnosed with advanced breast cancer, she struggled to juggle daughterly duties with work, a newborn child, her marriage, friends, and personal time. So even though Chryssoula was not a big tech person, she signed up to pilot test a new device that would constantly monitor her emotional state.

The ubiquitous devices in our pockets and on our wrists have been blamed for making us miserable. With their glowing screens and constant pings, they keep us hooked on a steady stream of office updates and Facebook likes. But what if these digital appendages could be used to improve mental health? That’s the promise of the Sentio’s Feel program: a wristband and phone app that track users’ emotional states, offer regular mental and physical exercises, and connect them to a therapist once a week.

The sensors in the wearable measure changes in heart rate, galvanic skin response, temperature, and movement.

The system uses artificial intelligence (AI) and the latest research in psychology to partner with both wearers and counselors, providing treatment that is simultaneously accessible, accurate, and personalized. “It’s data-driven therapy, which is such a huge plus in terms of evidence-based practice,” says Sharon Kaplow, a licensed clinical social worker and Sentio’s lead therapist.

Sentio’s founders, George Eleftheriou and Haris Tsirmpas, saw the need for improved mental healthcare based on their own experiences. Eleftheriou suffered from burnout and depression, while Tsirmpas endured unpredictable panic attacks. They both benefited from psychological counseling, while also observing holes in existing standards of care. Mental health assessment is highly subjective, and the focus on prevention is limited. Additionally, diagnoses are often missed, and there’s little real-time intervention.

Solving these problems would have a global impact. By some estimates, half a billion people worldwide have a mental illness, and the cost in the United States alone reaches $500 billion a year. Better options would benefit everyone: patients, therapists, insurance companies, and society.

Goals, Big and Small

Sentio’s solution offers a new approach to treatment. At its core is a wristband, the Feel Emotion Sensor, that is similar to the popular activity trackers worn by so many. But this tracker has four sensors that detect physiological reactions related to emotion. The sensors include a photoplethysmogram sensor, which measures changes in heart rate; a galvanic skin response (GSR) sensor, which measures perspiration; an infrared light sensor for measuring temperature; and an inertial measurement unit, which captures movement. The Feel Emotion Sensor continuously sends these signals via Bluetooth to the Feel app, which uploads them to a server in the cloud. The server contains proprietary AI algorithms that analyze the data and detect one of four emotional spaces: joy (positive, high energy), contentedness (positive, lower energy), distress (negative, high energy), and sadness (negative, lower energy).

Often, when Feel detects an emotion, the app will ask users to describe what’s happening and how they feel. That feedback serves three purposes: It helps the algorithm improve, it provides the therapist with richer information, and it prompts journaling, which brings greater self-insight. Chryssoula says the app "challenged me to be specific and analytical in the ways of improving myself, my negative thoughts, and my circling fears.”

The app might also suggest one of several exercises. For example, users might be asked to recall the key message from their last therapy session and describe how they plan to use that takeaway in their daily lives.

The Feel program lasts 16 weeks. Each week, the user has a video chat session with a licensed therapist who has confidential access to the user’s data through a software dashboard. Due to the data-driven approach, these sessions require only 15 minutes compared with the traditional 45. During the first session, they set up an overarching goal, along with a set of weekly subgoals, which, Kaplow says, are meant to increase accountability and make the big goal more digestible.

If the big goal, for example, is to take on a new leadership role at work, a subgoal might be to first look for opportunities to contribute, then figure out how to contribute, then tune into any self-defeating thoughts. Concrete functional goals can sometimes reveal more emotional goals, Kaplow says. The app’s cognitive behavioral therapy exercises can help users achieve those goals.

The Feel Program includes a phone app that tracks users’ emotional states, recommends strategies, and ask the users to describe what’s happening. This information is used in the weekly sessions with a Feel therapist.

AI algorithms analyze the data from the Feel Emotion Sensor and detect one of four emotions: joy, contentedness, distress, and sadness.

Users report any problems back to the therapist. Kaplow says a client who can’t speak up in a meeting might say: “‘Even though I was challenging my thinking, my heart was racing, my mouth was dry, I just couldn’t do it.’ So, then we would explore, ‘What could you do differently next time? What’s going to help you manage what’s going on physically for you?’ That’s where some of the exercises come in.”

Chryssoula’s main goal was to improve connections with family and friends. “Using the goals, I found ways to have more substantial and productive time with both my mother and my child,” she says. “I arranged at least one weekly outing with best friends.”

She also saw improvement in other areas of life. “I performed successfully in a demanding and stressful project at work, and also found a little time for relaxing and doing other things.”

Sifting for Signals

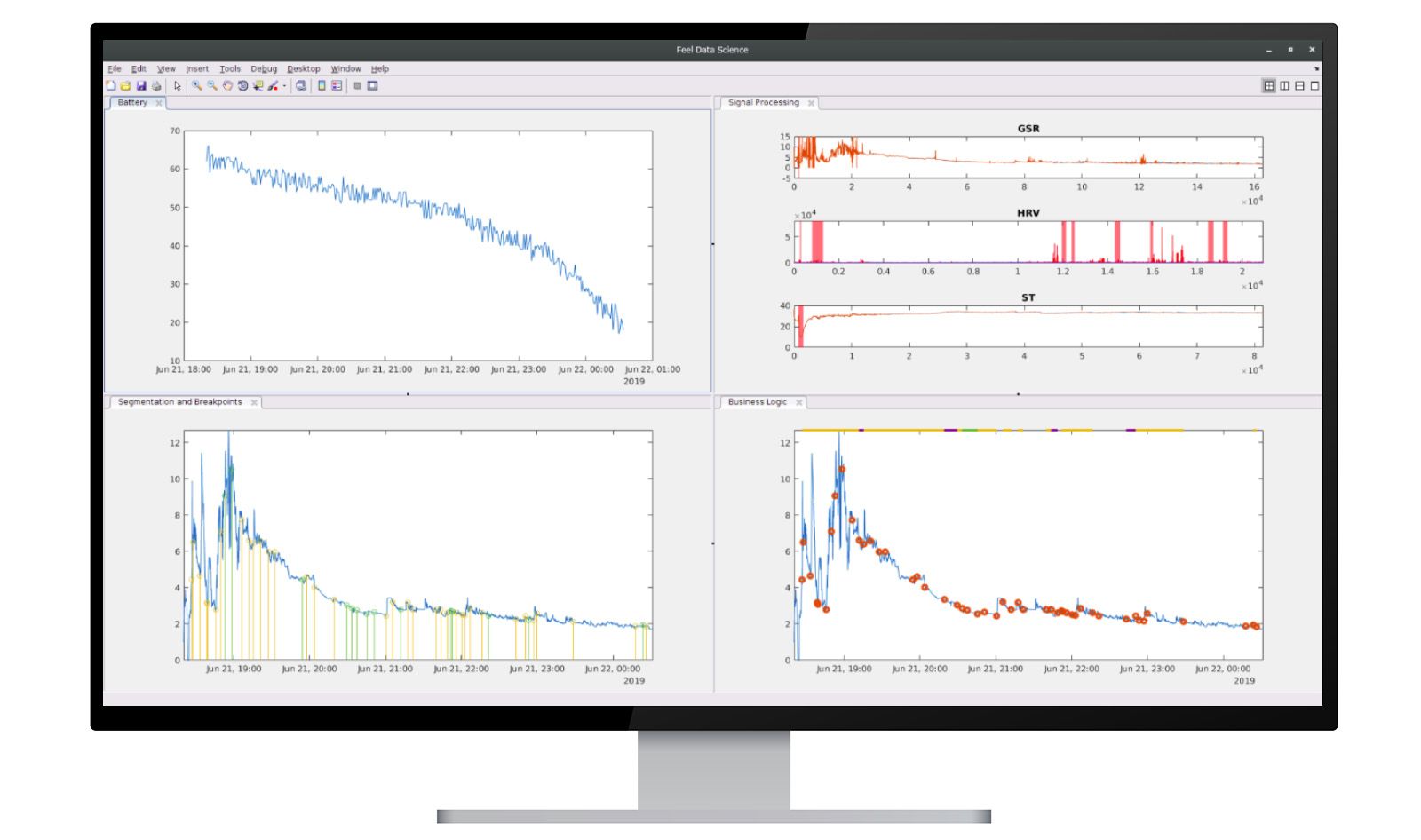

In designing Feel, "the biggest challenge was the need to translate a time series of physiological data into a crisp and concrete decision—the labeling of an emotion,” Tsirmpas says. To do so, they developed both the AI and the signal-processing algorithms in MATLAB®.

Machine learning and signal processing algorithms use physiological data captured by the Feel Emotion Sensor to detect emotions.

“The biggest challenge was the need to somehow translate a continuous flow of physiological data into a crisp and concrete decision—the labeling of an emotion.”

The first step in signal processing is preprocessing to remove extraneous noise. For physiological data, you might filter out any fluctuations caused by walking. Then comes data transformation, which finds important patterns in the data. These higher-level patterns are easier for algorithms to work with than millions of independent data points.

Tsirmpas says they use MATLAB to clean noisy signals and to segment them into discrete emotional events. “It helps a lot to proceed fast and make something robust.”

Machine learning, a form of AI that is well suited for complex problems involving large amounts of data and lots of variables, is used for the event detection algorithms. The machine learning algorithms, features in MATLAB, identify patterns in the data, such as combinations of biomarkers that indicate the different emotional biomarkers. It is these cloud-based algorithms operating on Amazon Web Services (AWS) servers that monitor the emotional state of the patient and feed results back to the app.

To guide their machine learning algorithms, Sentio first started with psychology literature describing which physical signals are most indicative of which emotions. Then, they fine-tuned the models by asking people wearing the emotion sensor to describe their feelings. The models also classified the readings, and if the emotion labels differed from what the user described, the models updated themselves to work better next time. The system also adapts itself to each individual user. Kaplow says people have reported that they feel like the Feel Emotion Sensor is really getting to know them. Overall the system has been tested with hundreds of users.

In some cases, it may know them better than they know themselves. “Sometimes we’re not aware of our emotions,” Kaplow says. “Oftentimes, we’ll have clients come in and complain they have stomach issues or headaches, and they see these physical symptoms as completely independent from their emotions. And the hope with this entire combination is connecting your mind and body to help you tune in better to what’s going on for you.”

“Throughout the week,” Chryssoula says, “the Feel app helped me notice how I was feeling in each significant moment—bad or good—and how intense it was. That made me think of how to resolve my matters, and sometimes I used the proposed help, such as breathing exercises, which helped me out in stressful situations.”

The app provides an interactive emotional calendar which provides not only notifications and inputs but also an accurate emotional and psychological image of one’s self. Kaplow notes that Feel gives her a better picture of her clients, “but I think they have a better picture of themselves, which is more important.”

Kaplow sees Feel as a force multiplier for her services. “The technology brings a level of engagement and awareness that is so helpful. In traditional therapy, you see your therapist and then daily life happens the second you leave that session. Not having that little nudge throughout the week can slow down your improvement. The Feel Emotion Sensor and the app give that constant level of engagement. What you’re learning and what’s discussed is constantly on your radar.”

“The whole program was a surprise to me,” Chryssoula says, “since even though I spent only a short time weekly in psychotherapy, I was feeling that I was in a constant daily and interactive psychotherapy adapted perfectly to my daily life.”

Kaplow believes systems like Feel could solve many of the problems with mental health treatment highlighted earlier. “Traditional therapy involves looking back on what happened during the week and looking forward to what you can do. But this technology allows for real-time support in a way that traditional therapy can’t. My traditional clients text message me if there’s an issue, but it’s reliant on their reaching out to me.” With Feel, however, “the emotion sensor is reaching out to them.”

“When starting the program, I could not imagine such positive impact,” Chryssoula says. “I learned that the first step to handle any complicated situation is to handle the way you think and feel.”