Optimizing Tuberculosis Treatment Using Nonlinear MPC with Custom Solver

This example shows how to find the optimal policy to treat a population with two-strain tuberculosis (TB) by constructing a nonlinear MPC problem. The nonlinear MPC controller then uses both the default solver and a custom solver to calculate the optimal solution.

Two-Strain Tuberculosis Model

A two-strain tuberculosis model is introduced in [1]. The model is described as follows:

"In the absence of an effective vaccine, current control programs for TB have focused on chemotherapy. The antibiotic treatment for an active TB (with drug-sensitive strain) patient requires a much longer period of time and a higher cost than that for those who are infected with sensitive TB but have not developed the disease. Lack of compliance with drug treatments not only may lead to a relapse but to the development of antibiotic resistant TB - one of the most serious public health problems facing society today. The reduction in cases of drug sensitive TB can be achieved either by "case holding", which refers to activities and techniques used to ensure regularity of drug intake for a duration adequate to achieve a cure, or by "case finding", which refers to the identification (through screening, for example) of individuals latently infected with sensitive TB who are at high risk of developing the disease and who may benefit from preventive intervention Description of first code block. These preventive treatments will reduce the incidence (new cases per unit of time) of drug sensitive TB and hence indirectly reduce the incidence of drug resistant TB."

In the dynamic model used in this example, the total host population N (which is a constant) is divided into six distinct epidemiological classes. Five of these classes are defined as state variables:

x(1) =

S, number of susceptible individualsx(2) =

T, number of effectively treated individualsx(3) =

L2, latent, infected with resistant TB but not infectiousx(4) =

I1, infectious with typical TBx(5) =

I2, infectious with resistant TB

The sixth class, L1 (latent, infected with typical TB but not infectious) is calculated as N - (S+T+L2+I1+I2).

You can reduce resistant TB cases using two manipulated variables (MVs):

u(1) - "case finding", relatively inexpensive effort expended to identify those needing treatment.

u(2) - "case holding", relatively costly effort to maintain effective treatment.

For more information on the dynamic model, see ResistantTBStateFcn.m.

Nonlinear Control Problem

The goal of TB treatment is to reduce the latent (L2) and infectious (I2) individuals with resistant TB during a five-year period while keeping the cost low. To achieve this goal, use a cost function that sums the following value over five years.

F = L2 + I2 + 0.5*B1*u1^2 + 0.5*B2*u2^2

Here, weight B1 is 50, and weight B2 is 500. These weights emphasize a preference for case finding over case holding due to its cost impact.

The total population is N = 30000. At the initial condition:

S = 19000 T = 250 L2 = 500 I1 = 1000 I2 = 250

which leaves L1 = 9000.

N = 30000; x0 = [76; 1; 2; 4; 1]*N/120;

In this example, find the optimal control policy using a nonlinear MPC controller. Create the nlmpc object with correct numbers of states, outputs, and inputs.

nx = 5; ny = nx; nu = 2; nlobj = nlmpc(nx,ny,nu);

Zero weights are applied to one or more OVs because there are fewer MVs than OVs.

Assume that the treatment policy can only be adjusted every three months. Therefore, set the controller sample time to 0.25 years. Since you want to find the optimal policy over five years, set the prediction horizon to 20 steps (5 years divided by 0.25).

Years = 5; Ts = 0.25; p = Years/Ts; nlobj.Ts = Ts; nlobj.PredictionHorizon = p;

For this planning problem, you want to use the maximum number of decision variables. To do so, set the control horizon equal to the prediction horizon.

nlobj.ControlHorizon = p;

The prediction model is defined in ResistantTBStateFcn.m. Specify this function as the controller state function.

nlobj.Model.StateFcn = 'ResistantTBStateFcn';

It is best practice to specify analytical Jacobian functions for prediction model and cost/constraint functions. For details on the Jacobian calculation for the state equations, see ResistantTBStateJacFcn.m. Set this file as the state Jacobian function.

nlobj.Jacobian.StateFcn = 'ResistantTBStateJacFcn';

Because all the states are numbers of individuals, they must be nonnegative values. Specify a minimum bound of 0 for all states.

for ct = 1:nx nlobj.States(ct).Min = 0; end

Because there is a large population variation among the groups (states), scale the state variables using their respective nominal values. Doing so improves the numerical robustness of the optimization problem.

for ct = 1:nx nlobj.States(ct).ScaleFactor = x0(ct); end

Both "finding" and "holding" controls have an operating range between 0.05 and 0.95. Set these values as the lower and upper bounds for the MVs.

nlobj.MV(1).Min = 0.05; nlobj.MV(1).Max = 0.95; nlobj.MV(2).Min = 0.05; nlobj.MV(2).Max = 0.95;

The cost function, which minimizes the TB population and the treatment cost, is defined in ResistantTBCostFcn.m. Since this planning problem does not require reference tracking or disturbance rejection, replace the standard cost using this cost function.

nlobj.Optimization.CustomCostFcn = "ResistantTBCostFcn";

nlobj.Optimization.ReplaceStandardCost = true;

Also, to speed up simulation, the analytical Jacobian of the cost is provided in ResistantTBCostJacFcn.

nlobj.Jacobian.CustomCostFcn = "ResistantTBCostJacFcn";

Since the L1 population is defined as N minus the sum of all states, you must ensure that (S+T+L2+I1+I2) - N < 0 is always satisfied. In the nlmpc object, specify this condition as an inequality constraint using an anonymous function.

nlobj.Optimization.CustomIneqConFcn = @(X,U,e,data) sum(X(2:end,:),2)-30000;

To check for potential numerical issues, validate your prediction model, custom functions, and Jacobians using the validateFcns command.

validateFcns(nlobj,x0,[0.5;0.5])

Model.StateFcn is OK. Jacobian.StateFcn is OK. No output function specified. Assuming "y = x" in the prediction model. Optimization.CustomCostFcn is OK. Jacobian.CustomCostFcn is OK. Optimization.CustomIneqConFcn is OK. Analysis of user-provided model, cost, and constraint functions complete.

To compute the optimal control policy, use the nlmpcmove function. At the initial condition, the MVs are zero. By default, fmincon from the Optimization Toolbox™ is used as the default NLP solver.

lastMV = zeros(nu,1); [~,~,Info] = nlmpcmove(nlobj,x0,lastMV);

Slack variable unused or zero-weighted in your custom cost function. All constraints will be hard.

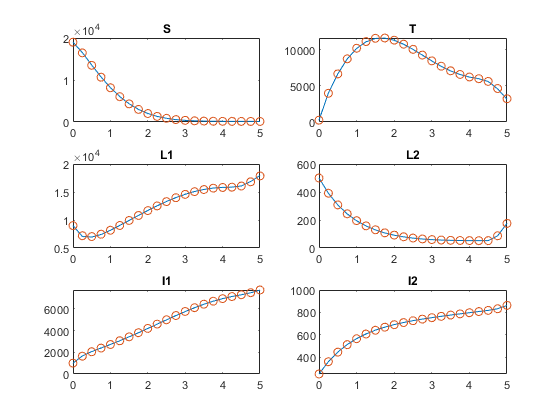

Plot and examine the optimal solution.

ResistantTBPlot(Info,Ts)

Optimal cost = 106.2 Final L2 = 766.4 Final I2 = 2843.7

The optimal solution yields a cost of 5195, and the total number of individuals infected with resistant TB at the final time is L2 + I2 = 1037.

Find Optimal Treatment Using Custom Nonlinear Programming Solver

If you want to use a third-party NLP solver in the simulation, write an interface file that converts the inputs defined by nlmpc into the inputs defined by your NLP solver, and specify it as the CustomSolverFcn in the nlmpc object.

In this example, assume that you have an "XYZ" solver that has a different user interface than fmincon. A ResistantTBSolver.m file is created to convert the optimization problem defined by nlmpc object to the proper interface required by the "XYZ" solver. Review the ResistantTBSolver.m.

function [zopt,cost,exitflag] = ResistantTBSolver(FUN,z0,A,b,Aeq,beq,lb,ub,NONLINCON) % This is an interface function that calls a XYZ nonlinear programming % solver to solve an NLP problem defined by an nlmpc controller. The % input and output definitions of this function are identical to fmincon. % % This interface function converts fmincon inputs to the format required % by the XYZ solver and converts the results back to the fmincon outputs. % % Inputs % FUN: nonlinear cost. FUN accepts input z (decision variabls) and % returns cost f (a scalar value evaluated at z) and its % gradient g (a nz-by-1 vector evaluated at z). % z0: initial guess of z % A,b: A*z<=b % Aeq,beq: Aeq*z==beq % lb,ub: lower and upper bounds of z % NONLINCON: nonlinear constraints. NONLINCON accepts input z and returns % the vectors C and Ceq as the first two outputs, representing % the nonlinear inequalities and equalities respectively where % FUN is minimized subject to C(z) <= 0 and Ceq(z) = 0. % NONLINCON also returns Jacobian matrices of C (a nz-by-ncin % sparse matrix) and Ceq (a nz-by-nceq sparse matrix). % % Outputs % zopt: optimal solution of z % cost: optimal cost at optimal z % exitflag: % 1 First order optimality conditions satisfied. % 0 Too many function evaluations or iterations. % -1 Stopped by output/plot function. % -2 No feasible point found. % % You can use this example as a template to implement an interface file to % your own NLP solver. The solver must be an M file or a MEX file on the % MATLAB path. % % DO NOT EDIT LINES ABOVE. % % Copyright 2018 The MathWorks, Inc. %% Set dimensional information of linear and nonlinear constraints num_lin_ineq = size(A,1); num_lin_eq = size(Aeq,1); [in,eq] = NONLINCON(z0); num_non_ineq = length(in); num_non_eq = length(eq); total = num_non_ineq + num_non_eq + num_lin_ineq + num_lin_eq; logicals_nlineq = false(total,1); logicals_nlineq(1:num_non_ineq) = true; logicals_nleq = false(total,1); logicals_nleq(num_non_ineq+(1:num_non_eq)) = true; logicals_ineq = false(total,1); logicals_ineq(num_non_ineq+num_non_eq+(1:num_lin_ineq)) = true; logicals_eq = false(total,1); logicals_eq(num_non_ineq+num_non_eq+num_lin_ineq+(1:num_lin_eq)) = true; options = struct('nlineq',logicals_nlineq,'nleq',logicals_nleq,... 'ineq',logicals_ineq,'eq',logicals_eq); %% Set decision variable bounds options.lb = lb; options.ub = ub; %% Set RHS of nonlinear constraints options.cl = [-inf(num_non_ineq,1);zeros(num_non_eq,1)]; options.cu = [zeros(num_non_ineq,1);zeros(num_non_eq,1)]; %% Set RHS of linear constraints options.rl = [-inf(num_lin_ineq,1);beq]; options.ru = [b;beq]; %% Set A matrix options.A = sparse([A; Aeq]); %% Set XYZ solver optons options.algorithm = struct('print_level',0,'max_iter',200,... 'max_cpu_time',1000,'tol',1.0000e-06,... 'hessian_approximation','limited-memory'); %% Set function handles used by XYZ solver Jstr = sparse(ones(num_non_ineq+num_non_eq,length(z0))); funcs = struct('objective',@(x) fval(FUN,x),... 'gradient',@(x) gval(FUN,x),... 'constraints',@(x) conval(NONLINCON,x),... 'jacobian',@(x) jacval(NONLINCON,x),... 'jacobianstructure',@() Jstr... ); %% Call XYZ and return cost and status [zopt,output] = XYZsolver(z0,funcs,options); cost = FUN(zopt); exitflag = convertStatustoExitflag(output.status); %% Utility functions function f = fval(fun,z) % Return nonlinear cost [f,~] = fun(z); function g = gval(fun,z) % Return cost gradient [~,g] = fun(z); function c = conval(nonlcon,z) % Return nonlinear constraints [in,eq] = nonlcon(z); c = [in;eq]; function J = jacval(nonlcon,z) % Return constraints Jacobian as nc-by-nz in sparse matrix % Jin is nz-by-ncin sparse, Jeq is nz-by-nceq sparse [~,~,Jin,Jeq] = nonlcon(z); J = [Jin Jeq]'; function exitflag = convertStatustoExitflag(status) switch(status) case 0 %info.Status = 'Success'; exitflag = 1; case 1 %info.Status = 'Solved to Acceptable Level'; exitflag = 1; case 2 %info.Status = 'Infeasible'; exitflag = -1; case 3 %info.Status = 'Search Direction Becomes Too Small'; exitflag = -2; case 4 %info.Status = 'Diverging Iterates'; exitflag = -2; case 6 %info.Status = 'Feasible Point Found'; exitflag = 1; case -1 %info.Status = 'Exceeded Iterations'; exitflag = 0; case -4 %info.Status = 'Max Time Exceeded'; exitflag = 0; otherwise %info.Status = 'IPOPT Error'; exitflag = -2; end

You can use this file as a template to implement an interface file to your own NLP solver. The solver must be a MATLAB® script or MEX file on the MATLAB path.

You can plug in the solver by specifying it as the custom solver in the nlmpc object.

nlobj.Optimization.CustomSolverFcn = @ResistantTBSolver;

As long as the "XYZ" solver is reliable and its options are properly chosen, rerunning the simulation should produce similar results.

References

[1] Jung, E., S. Lenhart, and Z. Feng. "Optimal Control of Treatments in a Two-Strain Tuberculosis Model." Discrete and Continuous Dynamical Systems, Series B2, 2002, pp. 479-482.