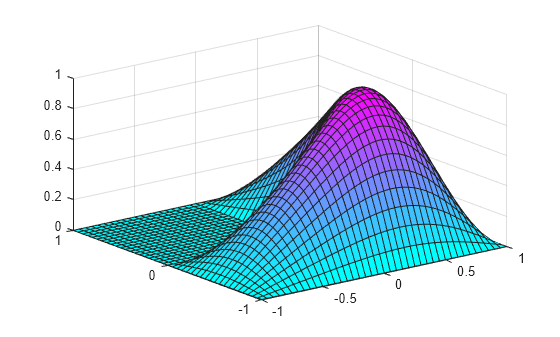

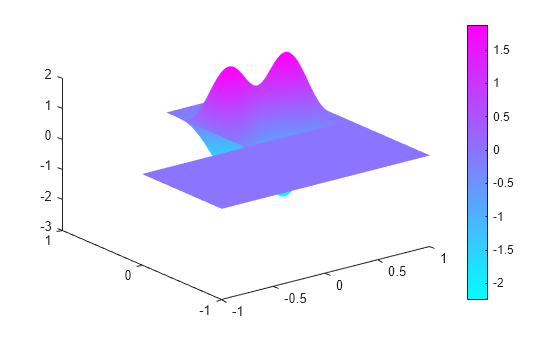

Partial Differential Equation Toolbox™ software handles the following basic eigenvalue problem:

where λ is an unknown complex number. In solid mechanics, this is a

problem associated with wave phenomena describing, e.g., the natural modes of a vibrating

membrane. In quantum mechanics λ is the energy level of a bound state in

the potential well a(x), where x represents a 2-D or 3-D point.

The numerical solution is found by discretizing the equation and solving the resulting

algebraic eigenvalue problem. Let us first consider the discretization. Expand

u in the FEM basis, multiply with a basis element, and integrate on

the domain Ω. This yields the generalized eigenvalue equation

where the mass matrix corresponds to the right side, i.e.,

The matrices K and M are produced by calling

assema for the equations

–∇ · (c∇u) + au = 0 and

–∇ · (0∇u) + du = 0

In the most common case, when the function d(x) is positive, the mass matrix M is positive definite

symmetric. Likewise, when c(x) is

positive and we have Dirichlet boundary conditions, the stiffness matrix

K is also positive definite.

The generalized eigenvalue problem, KU = λMU, is now solved by the Arnoldi algorithm applied to a

shifted and inverted matrix with restarts until all eigenvalues in the user-specified

interval have been found.

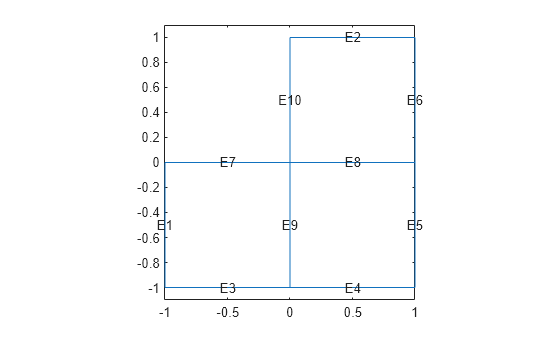

Let us describe how this is done in more detail. You may want to look at the examples

Eigenvalues and Eigenmodes of L-Shaped Membrane or Eigenvalues and Eigenmodes of Square, where actual runs are reported.

First a shift µ is determined close to where we want to find the

eigenvalues. When both K and M are positive definite,

it is natural to take µ = 0, and get the smallest eigenvalues; in other

cases take any point in the interval [lb,ub] where eigenvalues are

sought. Subtract µM from the eigenvalue equation and get (K - µM)U =

(λ - µ)MU. Then multiply with the inverse of this shifted matrix and get

This is a standard eigenvalue problem AU = θU, with the matrix A = (K – µM)-1M and eigenvalues

where i = 1, . . ., n. The largest eigenvalues

θi of the transformed matrix

A now correspond to the eigenvalues

λi = µ +

1/θi of the original

pencil (K,M) closest to the shift

µ.

The Arnoldi algorithm computes an orthonormal basis V where the shifted

and inverted operator A is represented by a Hessenberg matrix

H,

(The subscripts mean that Vj and

Ej have j columns and

Hj,j has j rows and

columns. When no subscripts are used we deal with vectors and matrices of size

n.)

Some of the eigenvalues of this Hessenberg matrix

Hj,j eventually give good approximations to

the eigenvalues of the original pencil (K,M) when the basis grows in

dimension j, and less and less of the eigenvector is hidden in the

residual matrix Ej.

The basis V is built one column

vj at a time. The first vector

v1 is chosen at random, as

n normally distributed random numbers. In step j,

the first j vectors are already computed and form the

n ×j matrix

Vj. The next vector

vj+1 is computed by

first letting A operate on the newest vector

vj, and then making the result orthogonal

to all the previous vectors.

This is formulated as , where the column vector hj

consists of the Gram-Schmidt coefficients, and

hj+1,j

is the normalization factor that gives

vj+1 unit length. Put the

corresponding relations from previous steps in front of this and get

where Hj,j is a

j×j Hessenberg matrix with the vectors

hj as columns. The second term on the

right-hand side has nonzeros only in the last column; the earlier normalization factors show

up in the subdiagonal of Hj,j.

The eigensolution of the small Hessenberg matrix H gives approximations

to some of the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of the large matrix operator

Aj,j in the following way. Compute

eigenvalues θi and eigenvectors

si of

Hj,j,

Then yi =

Vjsi

is an approximate eigenvector of A, and its residual is

This residual has to be small in norm for θi to

be a good eigenvalue approximation. The norm of the residual is

the product of the last subdiagonal element of the Hessenberg matrix and the last element

of its eigenvector. It seldom happens that

hj+1,j

gets particularly small, but after sufficiently many steps j there are

always some eigenvectors si with small last

elements. The long vector Vj+1

is of unit norm.

It is not necessary to actually compute the eigenvector approximation

yi to get the norm of the residual; we

only need to examine the short vectors si, and

flag those with tiny last components as converged. In a typical case n

may be 2000, while j seldom exceeds 50, so all computations that involve

only matrices and vectors of size j are much cheaper than those involving

vectors of length n.

This eigenvalue computation and test for convergence is done every few steps

j, until all approximations to eigenvalues inside the interval

[lb,ub] are flagged as converged. When n is much larger than

j, this is done very often, for smaller n more

seldom. When all eigenvalues inside the interval have converged, or when

j has reached a prescribed maximum, the converged eigenvectors, or

more appropriately Schur vectors, are computed and put in the front of

the basis V.

After this, the Arnoldi algorithm is restarted with a random vector, if all approximations

inside the interval are flagged as converged, or else with the best unconverged approximate

eigenvector yi. In each step j

of this second Arnoldi run, the vector is made orthogonal to all vectors in

V including the converged Schur vectors from the previous runs. This

way, the algorithm is applied to a projected matrix, and picks up a second copy of any

double eigenvalue there may be in the interval. If anything in the interval converges during

this second run, a third is attempted and so on, until no more approximate eigenvalues

θi show up inside. Then the algorithm

signals convergence. If there are still unconverged approximate eigenvalues after a

prescribed maximum number of steps, the algorithm signals nonconvergence and reports all

solutions it has found.

This is a heuristic strategy that has worked well on both symmetric, nonsymmetric, and

even defective eigenvalue problems. There is a tiny theoretical chance of missing an

eigenvalue, if all the random starting vectors happen to be orthogonal to its eigenvector.

Normally, the algorithm restarts p times, if the maximum multiplicity of

an eigenvalue is p. At each restart a new random starting direction is

introduced.

The shifted and inverted matrix A = (K –

µM)–1M is needed only

to operate on a vector vj in the Arnoldi

algorithm. This is done by computing an LU factorization,

using the sparse MATLAB® command lu (P and Q

are permutations that make the triangular factors L and

U sparse and the factorization numerically stable). This

factorization needs to be done only once, in the beginning, then x =

Avj is computed as,

with one sparse matrix vector multiplication, a permutation, sparse forward- and

back-substitutions, and a final renumbering.