测量信号相似性

此示例说明如何测量信号的相似性。它将帮助您回答诸如以下的问题:如何比较具有不同长度或不同采样率的信号?如何在测量中发现存在信号还是只存在噪声?两个信号是否相关?如何测量两个信号之间的延迟(以及如何将它们对齐)?如何比较两个信号的频率成分?也可以在信号的不同段中寻找相似性以确定信号是否为周期性信号。

比较具有不同采样率的信号

假设有一个音频信号数据库和一个模式匹配应用程序,您需要在歌曲播放时识别该歌曲。数据通常以低采样率存储,以占用较少的内存。

load relatedsig figure ax(1) = subplot(3,1,1); plot((0:numel(T1)-1)/Fs1,T1,"k") ylabel("Template 1") grid on ax(2) = subplot(3,1,2); plot((0:numel(T2)-1)/Fs2,T2,"r") ylabel("Template 2") grid on ax(3) = subplot(3,1,3); plot((0:numel(S)-1)/Fs,S) ylabel("Signal") grid on xlabel("Time (s)") linkaxes(ax(1:3),"x") axis([0 1.61 -4 4])

第一个和第二个子图显示来自数据库的模板信号。第三个子图显示我们要在数据库中搜索的信号。仅仅通过观察时间序列,该信号似乎与两个模板信号都不匹配。经仔细检查发现,这些信号实际上具有不同的长度和采样率。

[Fs1 Fs2 Fs]

ans = 1×3

4096 4096 8192

长度不同使您无法计算两个信号之间的差,但这可以通过提取信号的共同部分来轻松解决。此外,并不始终需要对长度进行均衡化处理。不同长度的信号之间可以执行互相关,但必须确保它们具有相同的采样率。最安全的做法是以较低的采样率对信号进行重采样。resample 函数在重采样过程中对信号应用一个抗混叠(低通)FIR 滤波器。

[P1,Q1] = rat(Fs/Fs1); % Rational fraction approximation [P2,Q2] = rat(Fs/Fs2); % Rational fraction approximation T1 = resample(T1,P1,Q1); % Change sample rate by rational factor T2 = resample(T2,P2,Q2); % Change sample rate by rational factor

在测量值中查找信号

现在,我们便可使用 xcorr 函数将信号 S 与模板 T1 和 T2 进行互相关,以确定是否存在匹配。

[C1,lag1] = xcorr(T1,S); [C2,lag2] = xcorr(T2,S); figure ax(1) = subplot(2,1,1); plot(lag1/Fs,C1,"k") ylabel("Amplitude") grid on title("Cross-Correlation Between Template 1 and Signal") ax(2) = subplot(2,1,2); plot(lag2/Fs,C2,"r") ylabel("Amplitude") grid on title("Cross-Correlation Between Template 2 and Signal") xlabel("Time(s)") axis(ax(1:2),[-1.5 1.5 -700 700])

第一个子图指示信号 S 和模板 T1 的相关性较低,而第二个子图中的高峰值指示该信号存在于第二个模板中。

[~,I] = max(abs(C2)); SampleDiff = lag2(I)

SampleDiff = 499

timeDiff = SampleDiff/Fs

timeDiff = 0.0609

互相关峰值意味着信号在 61 毫秒后开始出现在模板 T2 中。换句话说,模板 T2 比信号 S 超前 499 个采样,如 SampleDiff 所示。此信息可用于对齐信号。

测量信号之间的延迟并将它们对齐

假设您要从不同的传感器采集数据,这些传感器在桥的两边记录汽车引起的振动。当您分析信号时,您可能需要对齐它们。假设有 3 个传感器以相同的采样率工作并测量由同一事件引起的信号。

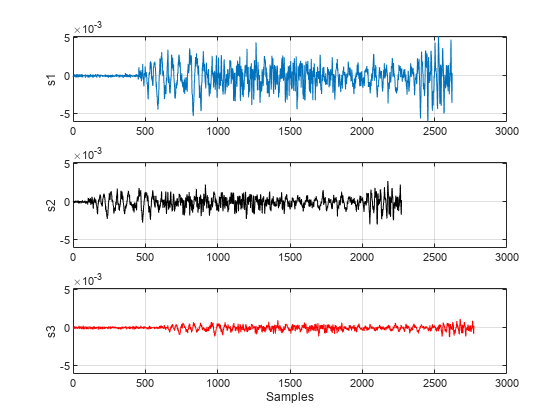

figure ax(1) = subplot(3,1,1); plot(s1) ylabel("s1") grid on ax(2) = subplot(3,1,2); plot(s2,"k") ylabel("s2") grid on ax(3) = subplot(3,1,3); plot(s3,"r") ylabel("s3") grid on xlabel("Samples") linkaxes(ax,"xy")

我们还可以使用 finddelay 函数来找到两个信号之间的延迟。

t21 = finddelay(s1,s2)

t21 = -350

t31 = finddelay(s1,s3)

t31 = 150

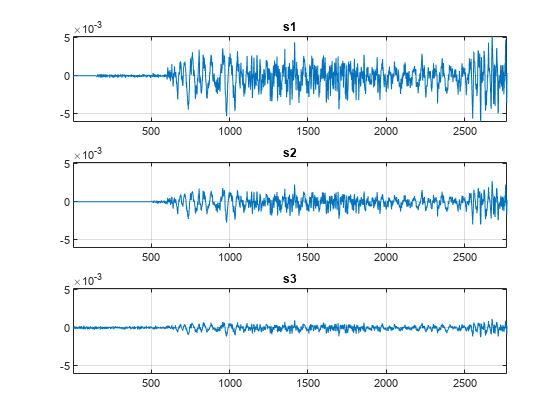

t21 表示 s2 比 s1 滞后 350 个采样,而 t31 表示 s3 比 s1 超前 150 个采样。现在可使用此信息通过时移信号来对齐这 3 个信号。我们还可以使用 alignsignals 函数,通过延迟最早的信号来对齐这些信号。

s1 = alignsignals(s1,s3); s2 = alignsignals(s2,s3); figure ax(1) = subplot(3,1,1); plot(s1) grid on title("s1") axis tight ax(2) = subplot(3,1,2); plot(s2) grid on title("s2") axis tight ax(3) = subplot(3,1,3); plot(s3) grid on title("s3") axis tight linkaxes(ax,"xy")

比较信号的频率成分

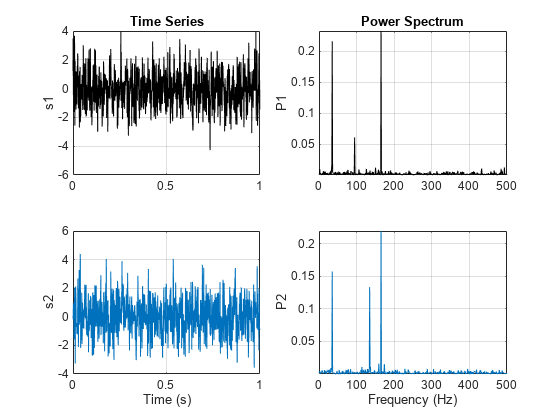

功率谱显示每个频率中存在的功率。频谱相干性确定信号之间的频域相关性。趋向于 0 的相干性值表示对应的频率分量不相关,而趋向于 1 的值表示对应的频率分量相关。假设有两个信号,它们各自的功率谱如下。

Fs = FsSig; % Sample Rate [P1,f1] = periodogram(sig1,[],[],Fs,"power"); [P2,f2] = periodogram(sig2,[],[],Fs,"power"); figure t = (0:numel(sig1)-1)/Fs; subplot(2,2,1) plot(t,sig1,"k") ylabel("s1") grid on title("Time Series") subplot(2,2,3) plot(t,sig2) ylabel("s2") grid on xlabel("Time (s)") subplot(2,2,2) plot(f1,P1,"k") ylabel("P1") grid on axis tight title("Power Spectrum") subplot(2,2,4) plot(f2,P2) ylabel("P2") grid on axis tight xlabel("Frequency (Hz)")

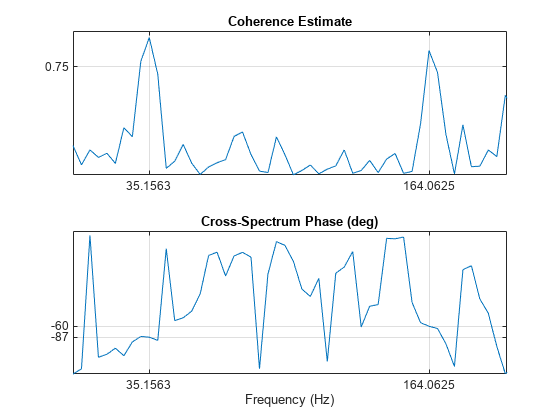

mscohere 函数计算两个信号之间的频谱相干性。该函数确认 sig1 和 sig2 在 35 Hz 和 165 Hz 附近有两个相关分量。在频谱相干性高的频率中,相关分量之间的相对相位可以用交叉频谱相位来估计。

[Cxy,f] = mscohere(sig1,sig2,[],[],[],Fs); Pxy = cpsd(sig1,sig2,[],[],[],Fs); phase = -angle(Pxy)/pi*180; [pks,locs] = findpeaks(Cxy,MinPeakHeight=0.75); figure subplot(2,1,1) plot(f,Cxy) title("Coherence Estimate") grid on hgca = gca; hgca.XTick = f(locs); hgca.YTick = 0.75; axis([0 200 0 1]) subplot(2,1,2) plot(f,phase) title("Cross-Spectrum Phase (deg)") grid on hgca = gca; hgca.XTick = f(locs); hgca.YTick = round(phase(locs)); xlabel("Frequency (Hz)") axis([0 200 -180 180])

35 Hz 分量之间的相位滞后接近 -90 度,165 Hz 分量之间的相位滞后接近 -60 度。

求信号的周期性

假设存在一组冬季办公楼的温度测量值。测量每 30 分钟进行一次,持续约 16.5 周。

load officetemp.mat Fs = 1/(60*30); % Sample rate is 1 sample every 30 minutes days = (0:length(temp)-1)/(Fs*60*60*24); figure plot(days,temp) title("Temperature Data") xlabel("Time (days)") ylabel("Temperature (Fahrenheit)") grid on

对于低于 70 度的温度,您需要去除均值来分析信号中的微小波动。xcov 函数在计算互相关性之前会删除信号的均值,然后返回互协方差。将最大滞后限制为信号的 50%,以获得互协方差的良好估计值。

maxlags = numel(temp)*0.5; [xc,lag] = xcov(temp,maxlags); [~,df] = findpeaks(xc,MinPeakDistance=5*2*24); [~,mf] = findpeaks(xc); figure plot(lag/(2*24),xc,"k",... lag(df)/(2*24),xc(df),"kv",MarkerFaceColor="r") grid on xlim([-15 15]) xlabel("Time (days)") title("Auto-Covariance")

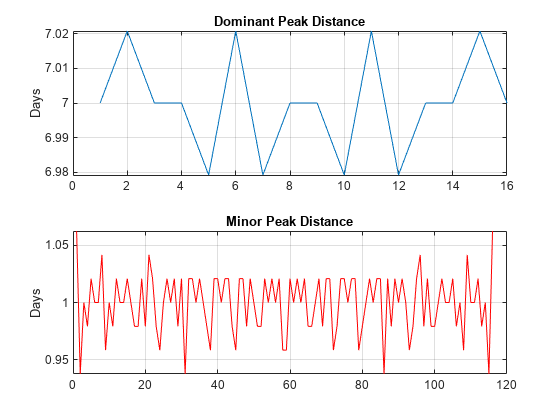

观察自协方差的主要和次要波动。主峰和次峰看起来是等距的。为了验证它们是否等距,请计算并绘制后续各峰值位置之间的差。

cycle1 = diff(df)/(2*24); cycle2 = diff(mf)/(2*24); subplot(2,1,1) plot(cycle1) ylabel("Days") grid on title("Dominant Peak Distance") subplot(2,1,2) plot(cycle2,"r") ylabel("Days") grid on title("Minor Peak Distance")

mean(cycle1)

ans = 7

mean(cycle2)

ans = 1

次峰指示每周有 7 个周期,而主峰指示每周有 1 个周期。这是合理的,因为数据来自以 7 天为日历周期的温控建筑物。第一个 7 天周期表明,建筑物温度存在以周为单位的周期行为,其中温度在周末较低,在工作日期间恢复正常。以 1 天为单位的周期行为表明,建筑物温度还存在以天为单位的周期行为,其中夜间温度降低,白天温度升高。

另请参阅

alignsignals | cpsd | finddelay | findpeaks | mscohere | xcov | xcorr